Michael Douglas, GHP of WA

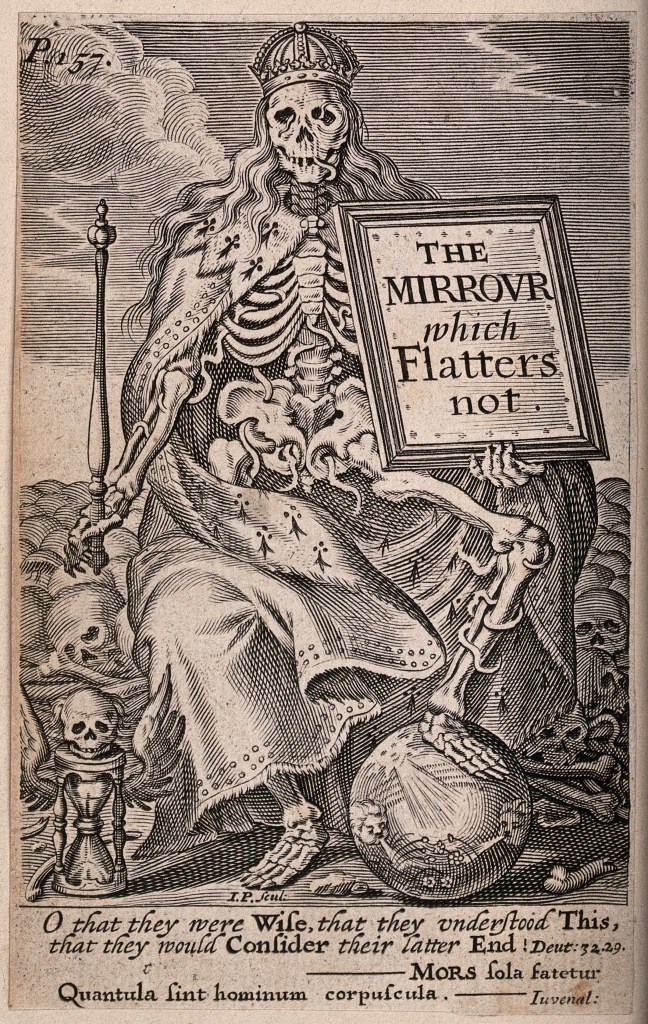

The Initiatory Degree is the doorway to Odd Fellowship. Its chief moral lesson is the consciousness of mortality. In fact, the contemplation of our own mortality is the starting point of many fraternal paths and wisdom traditions.

There are different ways to do this and also different levels on which to approach it. We can do this with intention or without. We are forced to do it by external circumstances periodically in our life when friends, or relatives, or people close to us die or are in danger of death. In moments of great transition in our lives – going through a divorce, losing a house, moving to a different town- we are brought face to face with the ephemeral nature of things in a very forceful way. This can easily bring up the awareness that we are living this life with a time limit.

On the simplest level, this can put things into perspective. It can help us prioritize our

lives. In the context of our lives being limited, things that are unimportant to us can drop away. This is a very useful level, and it’s a level that we don’t need to wait for extreme circumstances in our lives to put into effect. It’s an easy thing to remind ourselves of, to intentionally see things from that perspective.

There’s a deeper, more embodied level to consider. Many of our personality obstacles,

our defense mechanisms, are grounded in a kind of muscular and emotional contraction that’s based in our fight or flight instinct, our most primitive emotions around survival. The more we are aware of that reality, the more we are able to consciously go against that instinct, the more our automatic responses can relax and the more flexible we are. Gandhi said, “Those who defy death have no fear.” Those who refuse to let the fact of death configure their physical and emotional response to life will not be living life from a place of fear.

“Die before death” is an injunction attributed to the prophet Mohammed. St. Paul as well says, “I die daily”. This refers to the contemplative practice of consciously dying in one’s imagination and giving up attachment, knowing that all the things of this life will be ripped from us. Loosening attachment now allows us to approach life in a more comfortable way, because we’re no longer worried about holding on to things. This is what is meant by “spiritual poverty”. When Jesus said “Blessed are the poor in spirit”; when the Prophet said “Poverty is my pride”, they are referring to this practice of giving up ownership of everything we think is ours before it’s taken away from us, as it inevitably will be.

In accepting death and working to soften the survival instinct there is the possibility of

relaxing into reality. The more we accept life as it is, the more comfortable we are, and we will be coming from a place of relaxation rather than tension. Sam Lewis used to say, “The only sin is tension.” Because it’s tension that sustains our defenses and keeps us from listening, listening to each other and to what’s going on in the moment.

Rumi tells a story in the Masnavi about the death of the friends of God. When they die,

the angel of death comes, and stands at their bed, and politely offers to carry their luggage. There is a sense of ease in the transition. In the Jewish tradition it’s said that there are 903 ways to die, not physical ways to die, but ways to approach death. The hardest is compared to picking the thorns out of a ball of sheared wool. You have to tease each one out and it snags everywhere; there’s a visceral sense of entanglement in separating the soul and the body. The easiest is compared to removing a hair from a bowl of milk, the body being the hair and the soul the milk, because the soul is so much vaster than the body- and removing the body is like removing an obstacle for the soul. This is the death that is called, again in the rabbinic tradition, the “kiss of death”. This is the death that Moses died, and also the death that Miriam and Aaron died, where God takes the soul from the body with a kiss.

So we can become used to this idea of death, to the idea of leaving everything, through practicing being unattached in life. This doesn’t mean disengagement- but rather the sense of not owning things, of not having them own you. If we approach every day, as Mohammed said, like we are a traveler, like we are a stranger in this place, understanding that we can’t essentially own anything, then our transition into the next place is that much easier.

In the Christian narrative, after the crucifixion comes the resurrection. The Sufis talk about this in terms of annihilation and subsistence. Many traditions reference this pattern of giving everything up and consequently dealing with the world from a different perspective. And this isn’t just giving up material things, or just your body, it’s giving up attachment to everything that you think you are. Then when all of those structures relax, the Supreme Being can act through us. Something greater than ourselves can be alive through us, and then we get to experience that. This is an awakening which we will all experience eventually, but there’s something very different about experiencing it here and now, in the material plane, and in a human body.

As human beings, we can experience all the planes of existence from the highest to the lowest, and that can be an experience of great joy and power. And in a way, that experience is not just a gift of grace that God gives us; it’s a gift that we can give God. Or at least we could say that it begins to pay back in a small way everything that we have been given

Want to more about the Odd Fellows? Ask Me I May Know!

Visit our Facebook page: Heart In Hand