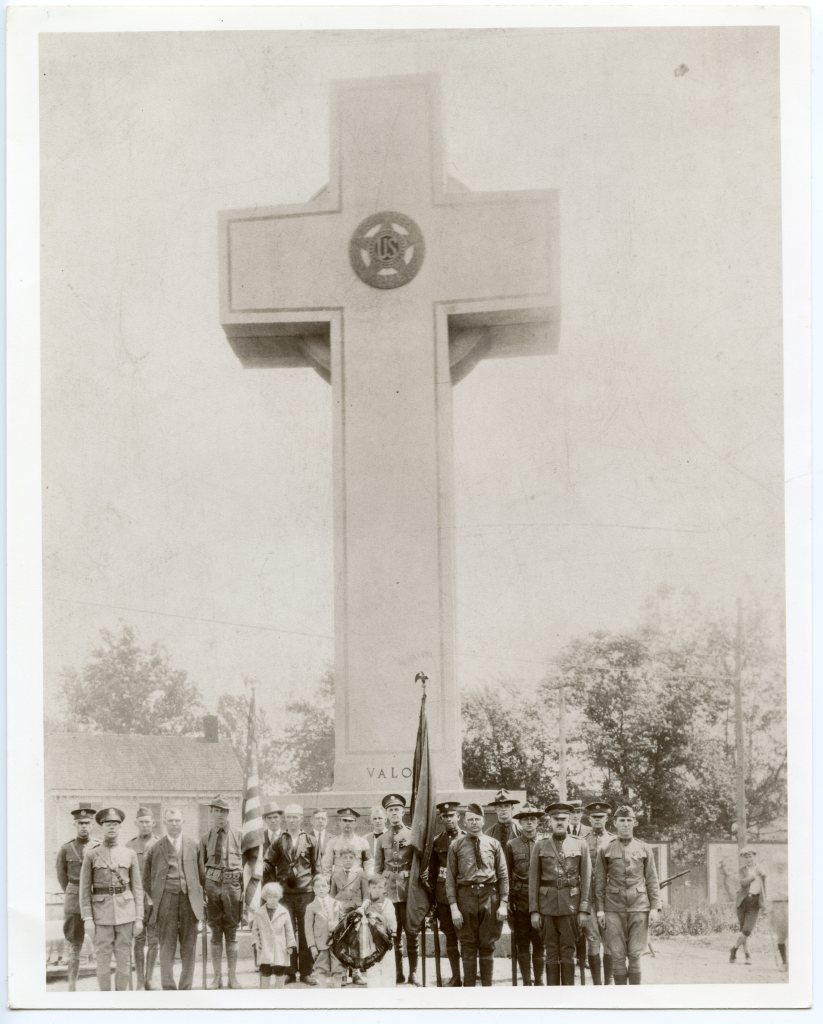

On July 13, 1925, Bernice Snyder watched as a military parade left Hyattsville’s Armory and marched down the street to Bladensburg, Maryland. The ceremony that day was to honor 49 men from Prince George’s county who died in World War One. The newly formed American Legion had just erected a 40-foot cross with the words Valor, Endurance, Courage, and Devotion etched into its stone. As the program continued throughout the afternoon, mayors, congressmen, and clergy stood up to address the crowd. Then, Bernice Snyder stepped forward and unveiled a bronze plaque at the base of the memorial, revealing the names of the fallen including her late son – Corporal Maurice Benjamin Snyder.

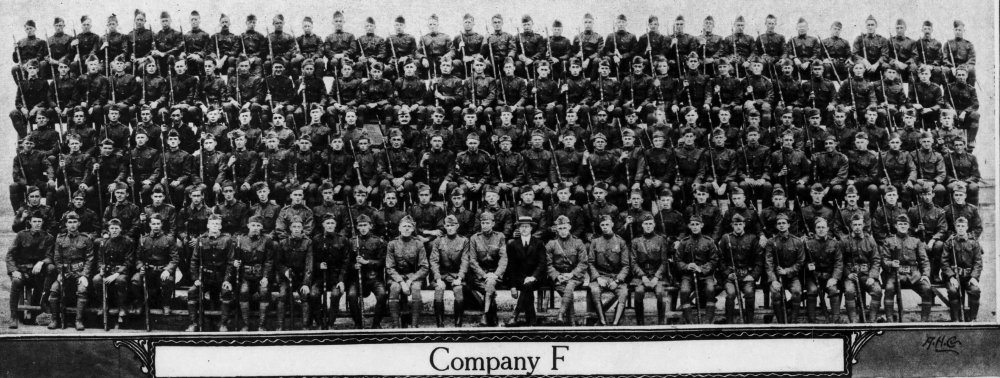

More than a decade earlier, in 1912, Oswald Augustus Greager organized Company F of the First Infantry Regiment in Hyattsville. Greager had at one point been the town’s mayor. He was an active member of Oriole Lodge No. 47 and even served as Noble Grand. But it was his role as a Captain in the Maryland National Guard that would prove to be the most impactful to Hyattsville’s history. That’s because the vast majority of lodge members or their immediate relatives who fought in the First World War served in Company F.

Originally, their unit operated out of a municipal building along with the fire department and various clerks. For a time, Company F only seemed to run drills and make headlines for their modest accomplishments. They won marksmanship competitions. They excelled at intramural basketball. “Hyattsville Company Best,” declared The Baltimore Sun in 1916. “Company F, of the First Regiment, stationed in Hyattsville, led not only the regiment, but the whole brigade in general excellence. It was given the excellent mark of 6 in appearance and neatness, steadiness in ranks, lines of formation, and in mechanism of fire direction and control.”

But as the great war in Europe dragged on, preparations were being made half a world away in Maryland. In Annapolis, while the state senate debated building large, dedicated armories, Company F earned special recognition for its high standards and excellent record. “Captain Greager of Company F is to be congratulated upon his record and has our sincere admiration as an officer of highest ability,” wrote The Democratic Advocate newspaper in 1916. “We hope that his company does secure an Armory this year…” But the Hyattsville Armory wouldn’t be built that year, and the men of Company F wouldn’t be there to see it happen.

When America declared war on Germany in April 1917, the U.S. Army had a mere 208,000 soldiers. Within two years, its ranks grew to 3.7 million. Among them was Maurice Benjamin Snyder and his older brother, Albert Snyder. They were the sons of Bradley and Bernice Snyder, two very active members of Oriole Lodge No. 47 and Esther Rebekah Lodge No. 20, respectively. In fact, of the 130 young men in Company F, at least 25 of them were lodge members or the children of lodge members. By retracing the movements of Company F, it’s possible to better understand the shared experience of this group of neighbors and fraternal brothers in an otherwise distant war.

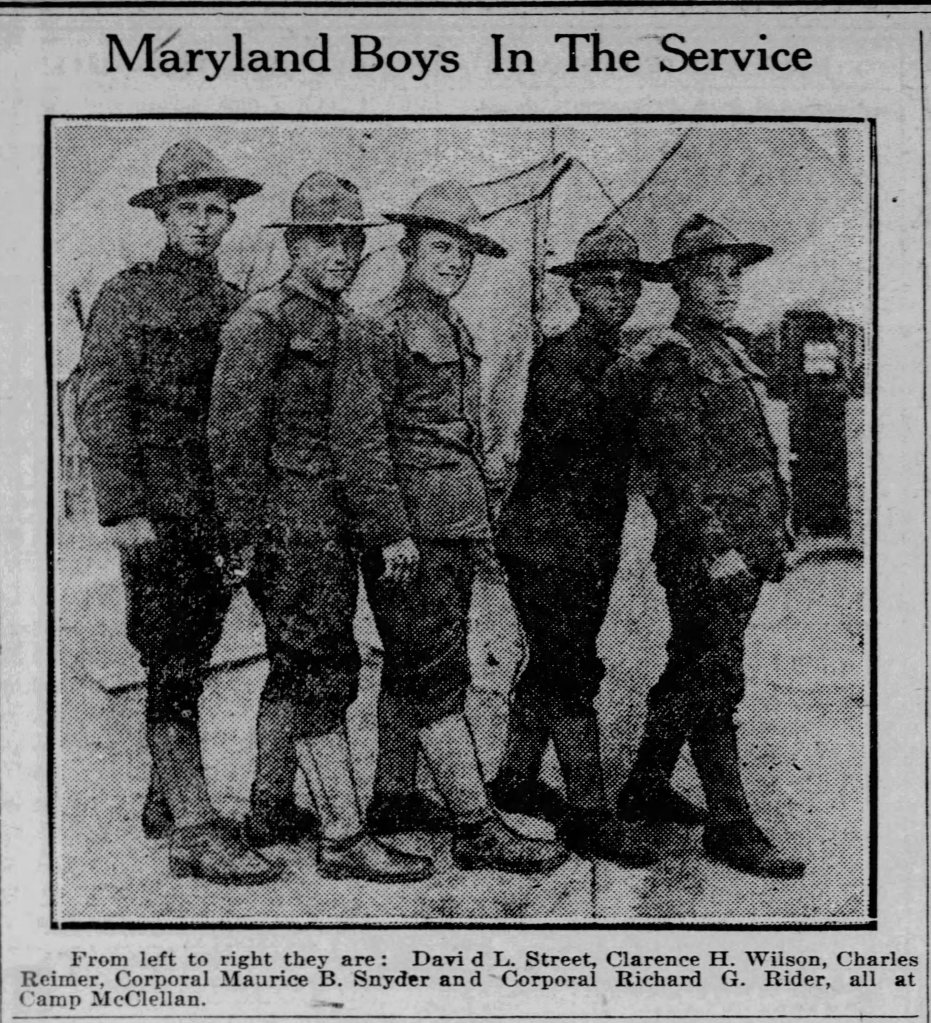

On July 10, 1917, Maurice Snyder signed up for Company F along with his friend, Carroll Franklin Stack. Maurice left business school to do so, while Carroll left a clerk job in a hardware store. On July 25, Company F was called into service. On August 5, National Guard units across the country were federalized including 6,900 soldiers from Maryland. The entire First Infantry Regiment was then sent to Alabama for the next year for training. “There they gathered full of hope and expectancy for a short period of training and then – across the water to lick the Hun! They never doubted for an instant their ability to do it,” one captain remembered. But the men were also told that warfare had fundamentally changed as a British Sergeant Major was on-hand to teach them bayonet techniques. Trained and reorganized, they were now part of a fighting force of 3,700 men with Marylanders at its core – the 115th Infantry Regiment of the 29th Division.

On June 15, 1918, Company F departed Hoboken, New Jersey aboard the U.S.S. George Washington. “Our trip across was very quiet, the weather was very calm, and submarines were not seen,” recalled one passenger. On June 27, the 115th Infantry Regiment arrived in St. Nazaire, France. On July 1, they boarded trains bound for the Western Front. At 3 a.m. on August 13, they awoke to German artillery firing on a nearby French position for 30 minutes straight. The next day, they began to engage in almost continuous trench warfare against the German Army. At first, they were stationed near Alsace in the middle of the country. There, they defended trenches and sent nightly patrols out into the inhospitable terrain of No Man’s Land. On three or four occasions, the men endured heavy artillery and gas attacks. The morning of September 19 was particularly notable for a 45-minute enemy artillery barrage starting at 6 a.m.

On October 1, the entire regiment was repositioned 120 miles northwest closer to Verdun. “Large dugouts were occupied while stationed at this point, on account of being in range of the large guns on the front. Many enemy aeroplanes were around. We remained here awaiting orders to proceed to the front line, to participate in the Meuse-Argonne battle, which had been started during the latter part of September,” a soldier wrote. On the afternoon of October 7, the 115th Infantry Regiment including Company F received orders to go into battle at 6 p.m. that day. While marching to the front in the rain, “shells were bursting around us at different places.” At 3 a.m., they relieved a French regiment in the trenches and tried to rest a little before that morning’s assault.

The Meuse-Argonne Offensive remains the largest offensive in U.S. military history as well as the deadliest. It lasted for 47 days along the entire Western Front and culminated in the end of the First World War. 1.2 million American servicemen took part in the fighting and there were 26,277 American deaths among 350,000 total casualties. This would ultimately involve 22 American divisions, 2,700 artillery pieces, 4 million artillery shells, 840 planes, and 324 tanks. Beginning on October 7, 1918, the 115th Regiment joined the battle and wouldn’t stop for the next 21 days. Serving alongside the French 18e Army Division, they fought to secure the heights on the Eastern side of the Meuse River. The terrain was difficult and varied including forests, riverbanks, and elevated ground. Worse still, enemy forces were securely dug in from having held this area for several years, giving them ample time to fortify 3 belts of trenches. The goal of the 115th was breakthrough those defenses and push the enemy back to Sivry-sur-Meuse and Flabas.

Here, the American 115th Infantry Regiment faced off against the Austrian 1st Infantry Division and the German 15th Infantry Division. The fighting began at 5 a.m. on the morning of October 8 with an hour-long American artillery barrage. Then, they moved forward and put their training to the test. While the 115th Infantry crushed Austrian forces in their initial advance, they met with fierce German resistance at the Consenvoye Woods and at Molleville Farm. This was in the form of counterattacks, heavy artillery, aerial bombardment, and nerve gas. Historian Michael Neiberg once wrote that, “The battle for the Meuse-Argonne turned into a massive campaign of attrition that the Americans could afford to fight, but the Germans could not.” Between October 2 and October 31, the 115th Infantry Regiment suffered 183 soldiers killed and 665 wounded. They advanced over six miles. And as a whole, their division took 2,148 prisoners and destroyed 250 enemy machine guns and artillery pieces.

This came at a great cost to Company F. Future lodge members Sergeant Hugh Thompson McClay and Sergeant John A. Johnson Jr. were among the wounded. So was Sergeant Percival Parlett Jr. But the only identifiable combat death with links to Oriole Lodge was that of Maurice Benjamin Snyder.

On October 9, 1918, Corporal Snyder and Private First Class Stack went over the top of the trench with their squad. According to a published excerpt from a letter written by Stack, Corporal Snyder “commanded them with coolness.” There was shelling and machine gunfire all around them. A German soldier appeared and threw a grenade at them. The blast “carried some of our men ten feet,” according to Stack. Snyder was shot and Stack’s right hand was badly injured, although newspaper accounts differ in their specific depiction of the fighting that ensued. As reported in The Baltimore Sun, Private First Class Stack avenged his friend by “drilling the beggar clean” with a bayonet through the chest, killing the German soldier. This attack most likely took place near the Consenvoye Woods. The next day, on October 10, the 115th Infantry Regiment advanced into the newly occupied ruins of Brabant-sur-Meuse.

On the day he died, Maurice’s parents received a letter from him, describing the dire situation in the trenches. It was their last communication. Bradley and Bernice Snyder would not actually learn of their son’s death until late November after the armistice had been signed and the war concluded. Corporal Maurice Benjamin Snyder was 18-years-old.

“Dear son, our hearts are broken with earthly sadness. Then we thank God for your faithful Christian life and remember you died for your country. We will meet again, where there is no sorrow. By his loving father and mother,” the couple wrote.

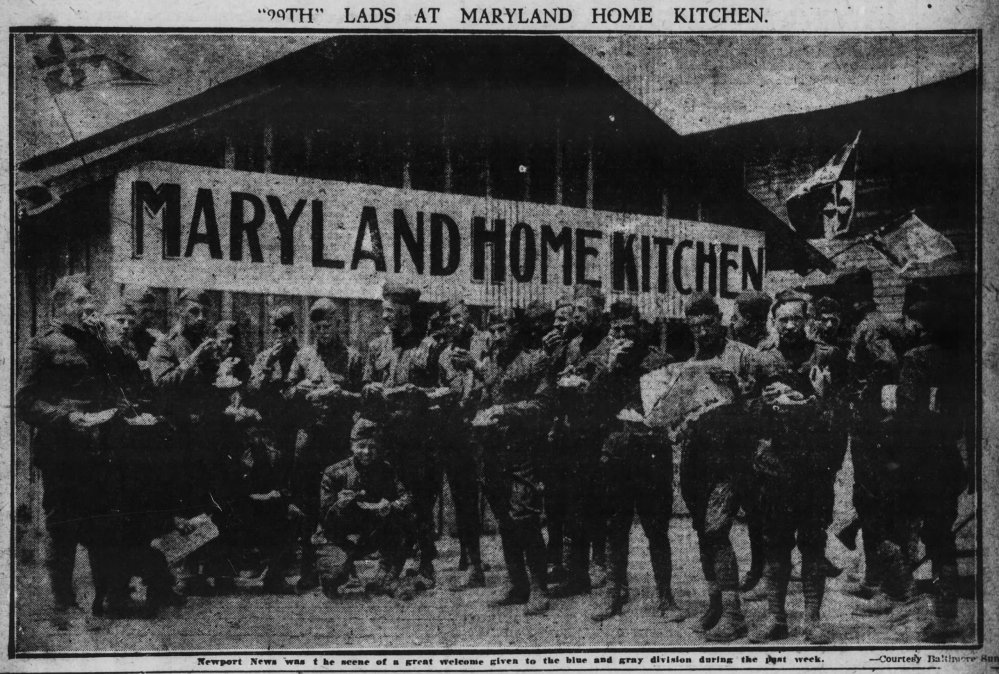

Months passed. On May 24, 1919, Company F arrived in Newport News, Virginia aboard the crowded U.S.S. Artemis. There, they were personally welcomed home by the Governor of Maryland. “Arrived, marched, deloused, ice-creamed, and put to bed!” declared the local newspaper, referring to the multi-course feast waiting for them when the men disembarked. “Gallant 115th Wins Many Decorations,” wrote another paper. Within days, the regiment paraded through the streets of Baltimore on their way to being demobilized at Camp Meade.

Then, on Saturday July 12, 1919, the men of Company F finally returned home to Hyattsville. “Big Day in Hyattsville,” The Baltimore Sun announced, “Returned Fighters Are Given a Rousing Welcome.” Edward Devlin, another former Mayor and Past Grand of Oriole Lodge, organized the day’s festivities. At 4 p.m., 1,000 soldiers marched down Wine and Franklin Avenues to the town’s new National Guard Armory, built in their absence. Hundreds of flags and decorations adorned the parade route, while thousands of people cheered. Older veterans joined the parade. The Governor of Maryland and other dignitaries presented medals and gave speeches. Then, the troops divided along segregated lines to separate banquets in their honor. “It was the greatest patriotic celebration ever staged in Prince George’s county, and an occasion that will go down to posterity as marking the deep and abiding affection and esteem held for the men and women who answered the call of duty,” wrote The Baltimore Sun.

Lodge members were there that day to welcome home their loved ones and fraternal brothers. Samuel Levin was there to see Private First Class Moses Levin. The Parlett family looked on at their son, Sergeant Percival Parlett Jr. Edward Devlin watched Seaman Second Class Edward Devlin Jr. march home in that grand procession. There was Captain James Moses Edlavitch, Captain Oswald Augustus Greager, and many more. For Bradley and Bernice Snyder though, there was some solace amidst the pain. Their oldest, Albert, had returned home from war even if their youngest, Maurice, had not. In total, the lodge lost four young men in the First World War: one member, Private Herman Elmer Burgess Jr. and three sons of its members including Lt. James Francis Quisenberry, Private First Class Thomas Notley Fenwick, and Corporal Maurice Benjamin Snyder. Yet, in spite of all the carnage across the Meuse-Argonne and other fronts, Maurice Snyder was the only one of those four to die in combat. The others fell in rapid succession to the Spanish Flu of 1918 that claimed so many lives.

Today, Hyattsville, Maryland is known for its distinct Armory building – now a church. Just down the road, the names of Maurice Benjamin Snyder, Herman Elmer Burgess Jr., James Francis Quisenberry, Thomas Notley Fenwick, and others appear on the memorial plaque of the Bladensburg Peace Cross. It stands there still. So does the Odd Fellows lodge where friends and family continue to gather. And while the headlines of a hundred years ago have long faded into history, it’s the lives touched by those events that endure all around us to be remembered in the community they built.

…

Want to more about the Odd Fellows? Ask Me I May Know!

Visit our Facebook page: Heart In Hand